The idea of this short trip has come from a PDF received from an archaeologist

friend, Alexandros Tsakos: a report of the “crossing” performed in 1999 by Krzysztof

Pluskota, polish archaeologist, and Arita Baaijens, writer and traveller.

They’ve left from Khartoum with 3 dromedaries along a 500 Km. path that really,

bypassing the mountain chains and looking for freshwater wells to water the

dromedaries, turned into 900 Km. It took them six weeks to get to the Red Sea

shores. One day, accidentally, while the dromedaries were grazing in a valley

nearby one of these wells, called by the local population “bir”, the two

travellers on the way back, patrolling the landscape onside, discovered several

graffiti of great interest. Here’s where my wish to reach the area originates,

departing from the opposite side, from where they’ve arrived, that is from

Dungonab and carry out a part of the trip, definitely shorter, backwards.

The idea of this short trip has come from a PDF received from an archaeologist

friend, Alexandros Tsakos: a report of the “crossing” performed in 1999 by Krzysztof

Pluskota, polish archaeologist, and Arita Baaijens, writer and traveller.

They’ve left from Khartoum with 3 dromedaries along a 500 Km. path that really,

bypassing the mountain chains and looking for freshwater wells to water the

dromedaries, turned into 900 Km. It took them six weeks to get to the Red Sea

shores. One day, accidentally, while the dromedaries were grazing in a valley

nearby one of these wells, called by the local population “bir”, the two

travellers on the way back, patrolling the landscape onside, discovered several

graffiti of great interest. Here’s where my wish to reach the area originates,

departing from the opposite side, from where they’ve arrived, that is from

Dungonab and carry out a part of the trip, definitely shorter, backwards. Not having much information, the wisest thing has been to look for news among the beja, the ethnic group occupying the area of the Red Sea since time immemorial; they are nomads and used to go through long distances with flocks or dromedaries. I’ve found my “expert” in Mohamed, lorry driver, all along used to travelling through valleys and mountains, carrying people and goods from a village to another one. Another chosen Mohamed Tala him too beja. Then Isa, professionally fisherman, who, after being my sailor many years ago, is sharing with me any tour.

As vehicle we’ve used a lorry, for the small cost and that special

quality consisting in having the chance to pick up people and goods during the

route, enriching ourselves with a variety of information, becoming more

involved in the landscape with its inhabitants, loosing, as far as possible,

the tourist awareness and sharing the eternal, unanimous going.

Then we’ve departed from Dungonab, village of fishermen and shepherds by the seaside 150 Km. up north Port Sudan. We’ve travelled 50 Km. on paved road, the one that then goes on northbound up to the Egyptian border, and we’ve turned westerly. We’ve passed through a first flat sandy stretch, studded with acacia up to the first mountain chain, our direction has always been West, and so we went on as much as cliffs, hills and broken mountains have allowed us, forcing us into a winding route valley by valley, wadi by wadi. The uneven landscape, mostly stony and desert, was studded, as we were progressively turning from the sea, with greater and greater and more impressive acacia, a different species compared to the ones on the coast. Splendid specimens were extending the unique delicate shadows in the valleys whitened by the sultry sun.

Then we’ve departed from Dungonab, village of fishermen and shepherds by the seaside 150 Km. up north Port Sudan. We’ve travelled 50 Km. on paved road, the one that then goes on northbound up to the Egyptian border, and we’ve turned westerly. We’ve passed through a first flat sandy stretch, studded with acacia up to the first mountain chain, our direction has always been West, and so we went on as much as cliffs, hills and broken mountains have allowed us, forcing us into a winding route valley by valley, wadi by wadi. The uneven landscape, mostly stony and desert, was studded, as we were progressively turning from the sea, with greater and greater and more impressive acacia, a different species compared to the ones on the coast. Splendid specimens were extending the unique delicate shadows in the valleys whitened by the sultry sun.

Left just before dawn, we’ve arrived at the Nurajet valley at about

three in the afternoon.

I reckon, between a short break to take refreshment and a couple of

covers-up, we have travelled zigzagging at least 350 Km. We’ve got off the

lorry after hours of jolting and jumping, vaguely banged up, but we immediately

recovered influenced by the spectacular fascination of the landscape. The

mountain of Magardi stands solitary in the middle of a wide and verdant “wadi”,

shaping in that stretch from South-Northwards. On the instant the image of

Angarosh has appeared, irrepressible: the legendary reef of the Sudanese Red

Sea, arising bright as a pinnacle from the depths, equal beauty and charm, with

its golden top framed with the bluest sea.

At dawn, when the oblique rays stand out the rocks and deepen the

shadows, it looks like the head of a brontosaurus rising from the earth wide

open as a treasure chest, with the mouth open towards the sky.

It dominates, almost as a totem, and it seems to grant, beneficial, the

most rare thing in these places: at its feet, on the North side, there are two

wells of precious freshwater. On the West side, perpendicular to the valley,

there are a few smaller “wadi” in a scenic design of dark rough rocks. The

following three days have passed distributed between systematic patrols in

these secondary valleys, climbing through slopes of collapsed rocks, from dawn

to midday and from three o’ clock in the afternoon to the sunset.

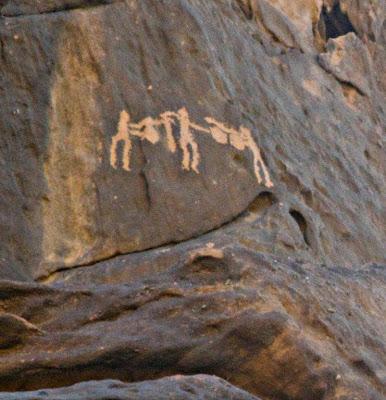

With the hot sun and boiling air, sheltering and resting in the shadow of the bushes and of the lorry and having breakfast, our “fatur”. We have found masses of graffiti representing buffalos with very long horns, single haughty males and fertile females characterised by big breasts, or herds, dromedaries, ostriches, antelopes, wild beasts. Several human figures sometimes on the back of a dromedary, attached to the end following a herd or in a battle attitude armed with lances, bows and shields. We have seen only one inexplicable beautiful elephant. The styles looked mainly four and they were often superimposed. Some animals were sketched, unrefined and primitive, some others very decorated and well refined and the details of the elegant coat and the colour variance were minutely designed with dotting. Sometimes they were hidden or hardly reachable, they were without any doubt living the mountain and were telling the silences…

With the hot sun and boiling air, sheltering and resting in the shadow of the bushes and of the lorry and having breakfast, our “fatur”. We have found masses of graffiti representing buffalos with very long horns, single haughty males and fertile females characterised by big breasts, or herds, dromedaries, ostriches, antelopes, wild beasts. Several human figures sometimes on the back of a dromedary, attached to the end following a herd or in a battle attitude armed with lances, bows and shields. We have seen only one inexplicable beautiful elephant. The styles looked mainly four and they were often superimposed. Some animals were sketched, unrefined and primitive, some others very decorated and well refined and the details of the elegant coat and the colour variance were minutely designed with dotting. Sometimes they were hidden or hardly reachable, they were without any doubt living the mountain and were telling the silences…

The Polish archaeologist, Krzysztof Pluskota, in his report, asserts

that this is the first clear expression of the life existence and sheep farming

activity in the Red Sea hills. The different superimposed styles demonstrate

that they have been made during a long period of time. And this is what it’s

perceived and imagined, given that the valley, even if besieged by the drying

up, still preserves the mild and ideal appearance of a small fertile Eden.

Perhaps someone thought to settle there, for sure many people passed through,

as carrying on north or southbound.

Waki Oko goes on northwards up to over the border with Egypt to flow almost into the sea in front of the Syal islands, whereas more westerly, through secondary wadi, it links with Allaqi wadi (the famous wadi where there are the remains of Berenice Pancrisia) getting to the Egyptian territory up to the Nile. Both routes have been traversed for exchanges and trades with the neighbouring brothers,

friends and enemies depending on the historical phases. The most interesting and significant has appeared in a small closed valley, protected by an arch of rocks, almost inaccessible and hidden, where the graffiti were even more numerous, nearly a choral play. “There’s not space for doubting that it was under a religious regime and that the real purpose was to multiply magically herds and flocks. This seems to be reinforced by the surrounding landscape where the isolated Jebel Magardi and the adjacent, fencing valley, create together natural symbols of fertility” as our inspiring polish archaeologist writes. We search around tripping along, as we really feel as if we’re walking on the past…

Waki Oko goes on northwards up to over the border with Egypt to flow almost into the sea in front of the Syal islands, whereas more westerly, through secondary wadi, it links with Allaqi wadi (the famous wadi where there are the remains of Berenice Pancrisia) getting to the Egyptian territory up to the Nile. Both routes have been traversed for exchanges and trades with the neighbouring brothers,

friends and enemies depending on the historical phases. The most interesting and significant has appeared in a small closed valley, protected by an arch of rocks, almost inaccessible and hidden, where the graffiti were even more numerous, nearly a choral play. “There’s not space for doubting that it was under a religious regime and that the real purpose was to multiply magically herds and flocks. This seems to be reinforced by the surrounding landscape where the isolated Jebel Magardi and the adjacent, fencing valley, create together natural symbols of fertility” as our inspiring polish archaeologist writes. We search around tripping along, as we really feel as if we’re walking on the past…

Every minute of the dense days was full of emotions. The rhythm of our

life was perfectly in harmony with the landscape and it naturally became

similar to the nomads one, travellers, beja,

inhabitants of the valley, all along, from time immemorial. Our meals were cooked with fire of wood collected around and were shared in one big platter where each one dipped into with bread. Sometime someone was passing by and sat down, joining the dining companions: a shepherd looking for his sheep, someone who was going down northbound, some others southbound, with dromedaries full of products to bring to be sold in a market or to the family in a village at an unspecified distance: “baiid”…far away…

inhabitants of the valley, all along, from time immemorial. Our meals were cooked with fire of wood collected around and were shared in one big platter where each one dipped into with bread. Sometime someone was passing by and sat down, joining the dining companions: a shepherd looking for his sheep, someone who was going down northbound, some others southbound, with dromedaries full of products to bring to be sold in a market or to the family in a village at an unspecified distance: “baiid”…far away…

Chatters, the grumble of the wind, were raising the same: in time, in

the night, among the stars, under the same sky.

It was a dead zone and therefore no mobile phones around; if someone did

not have a wristwatch, the sensation would have been that time had stopped to

slowly go on, as an undertow, in reverse. The ears of durum wheat depleted were

rippling not far away: a few days before the grasshoppers have passed through,

impossible not to think in a shiver at Ramses II and the curse…

Isa was telling that his dialect is not written, hading down from father

to son and that one day a researcher, gone through Dungonab, had numbered a few

Egyptian words, of the Pharaohs time, very similar as per pronunciation and the

same per meaning to some words of her beja language. A reason of great pride

for him and, during our night, a plot was creeping into tying tightly Pharaohs

and beja up to us…

Isa was telling that his dialect is not written, hading down from father

to son and that one day a researcher, gone through Dungonab, had numbered a few

Egyptian words, of the Pharaohs time, very similar as per pronunciation and the

same per meaning to some words of her beja language. A reason of great pride

for him and, during our night, a plot was creeping into tying tightly Pharaohs

and beja up to us… I read that the language of the Beja population, called Bedauj as well, probable descendant of the ancient “Blennidi”, is

typical in the Westside shore of the Red Sea, in the South West of Egypt, in the North East of Sudan, in Eritrea and North West of Etyopia: it belongs to the Cushitic branch. Isa was proudly telling with her eyes, in broad moonlight, how strong, brave and warlike they are. How overwhelming the yearning of freedom, the anarchy and the impossibility to be somehow placed into a system. The beja phonetics is typical of the Cushitic languages and the Egyptian language, one of the most ancient decoded languages known, before giving in to Copt and Arabic, it was even part of the Afro-Asian family and has connections with Berber, Semite and the beja indeed.

Thus, while the moon was going down, the shadows were reaching out, the

limit between past and present, magic and reality, was assuaging and dissolving

under a sky so crowded with stars to look light. The profile of the mountains,

the sandy stretch and the pale bushes, were perfectly perceived and in the

distance, now and then, there was someone still going.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento